Photo by Pushpins

With restaurants and coffee shops still operating on limited capacity due to safety precautions against Covid-19, everyone became their own barista. In fact, Data from Brandwatch shows a spike of interest for coffee machines in the U.S. A quick look at Google Trends shows the same thing happening in the Philippines. Searches for “coffee at home” peaked by the end of March 2020, two weeks after the entire region of Luzon was placed on lockdown. Good thing the different types of Philippine coffee are now easily accessible, thanks to the bevy of roasters and third-wave coffee shops that have popped up in recent months. This makes it easier to craft your own brew according to your specific preferences. After all, preparing your own cup of coffee is a comforting ritual—from grinding the beans and watching the grounds bloom, to finally tasting that fresh brew.

Home-grown goodness

The Philippines is no stranger to coffee bean production. The country used to be the fourth largest coffee exporter, with Lipa, Batangas touted as the coffee capital of the nation. Unfortunately, in 1889, the coffee rust decimated the coffee production of the country.

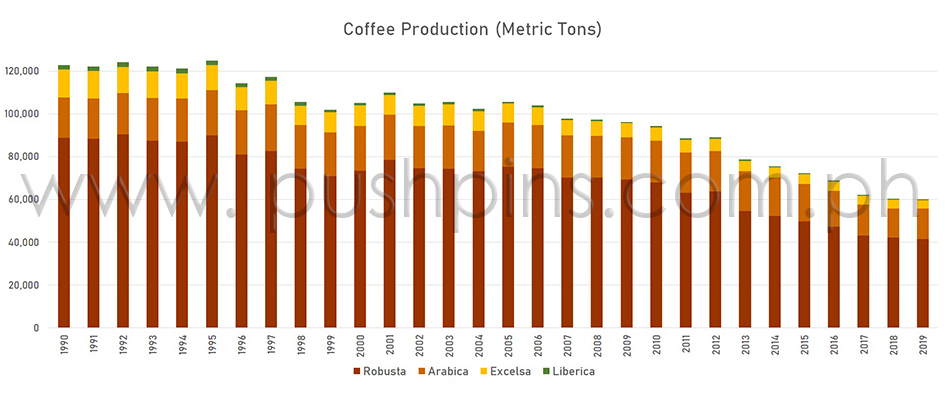

The Philippines is not able to recover from this tragedy, based on the data published by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) dating back from 1990. In fact, it appears that the volume of coffee production has been steadily declining. The average yield in the last few years is almost half of what was being produced from the early to mid-1990s.

Coffee production in the Philippines is seeing a slow decline in the past 30 years

That is not to say, though, that the Philippines lags behind in terms of coffee quality. While there is a prevailing misconception that all Filipino coffee is kapeng barako, the country actually takes pride in being one of the few to produce all four main varieties of coffee: robusta, arabica, excelsa, and liberica. “A lot of the varieties we have are heirloom varieties. They haven’t been [genetically modified]… Pure sila (They’re pure),” says Rosario “Ros” Juan, owner of Commune Café and member of the International Women’s Coffee Alliance.

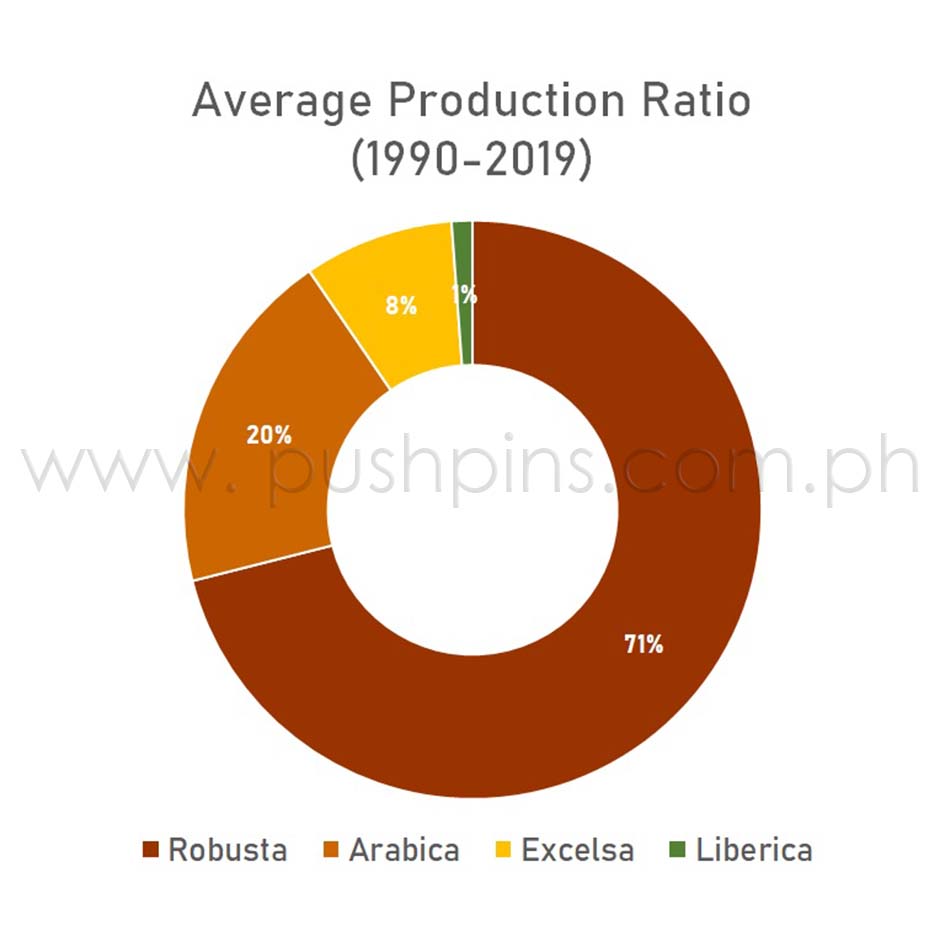

The archipelago’s topography makes it an ideal ground for growing all four kinds, with robusta as the more commonly grown among the lot.

Robusta is the widely produced coffee variant in the country, followed by arabica, excelsa, and liberica.

Robusta is the widely produced coffee variant in the country, followed by arabica, excelsa, and liberica.

Packing more punch

Commonly used in instant coffees, robusta has a lot more caffeine. That pack of 3-in-1 is, in fact, more potent than a single shot of espresso, according to Ros. When mixed with other bean variety, robusta gives the blend more body. It also gives that espresso cup its rich crema.

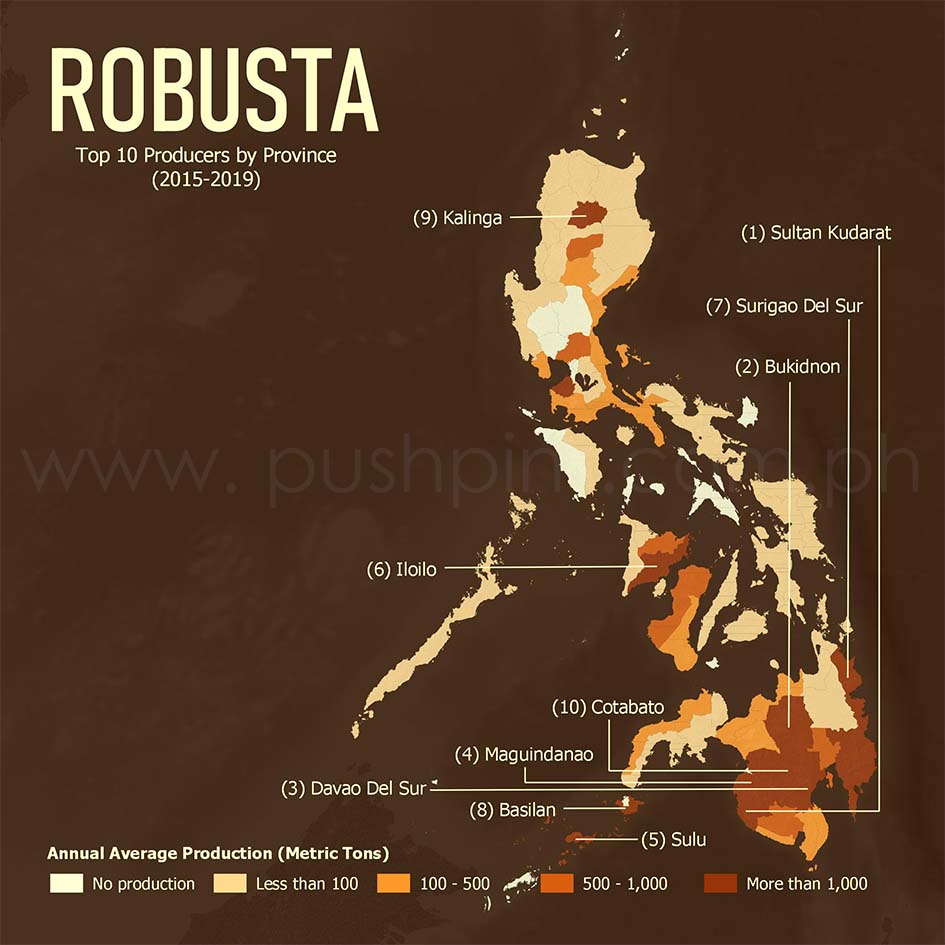

Because it is relatively easier to cultivate, robusta commands a more affordable price in the market. It is grown in the lowlands and is more robust when it comes to resisting diseases, hence the name.

In the last five years, almost 80% of Philippine robusta is produced in Mindanao. Eight of the top 10 provinces that cultivate robusta are from this region, with Sultan Kudarat as the country’s the top producer. Rounding up the top 10 are Kalinga (Luzon) and Iloilo (Visayas), with the latter supplying majority of its harvest to the instant coffee industry. Other provinces, such as Cavite, Ifugao, Capiz, Bulacan, and Nueva Vizcaya, also grow robusta.

Interest in fine robustas, albeit small, is growing, according to Ros. She relates, “May ibang players na gearing toward that. (There are other players gearing toward that.) In Iloilo, that’s La Granja Cereza Roja who supplies robusta to Coffee Brewtherhood. They sell it single origin but dark roast.” Sulu Royal Coffee in Mindanao also has fine robusta.

The bigwig

Arabica is the most popular variety, enjoying a high demand worldwide. Relates Ros, “It’s globally known, and it’s where the aroma really comes from. The complexity of flavors in arabica is quite amazing.” Good-quality arabica has a tinge of sweetness, with flavors of chocolate, nuts, caramel, and even hints of fruity notes.

“It also demands higher prices because it’s harder to grow. It grows in higher elevation,” Ros adds. “It needs more space between plants, so for example, when you plant, you can only grow so much. It needs a certain amount of rainfall, not too much sun.”

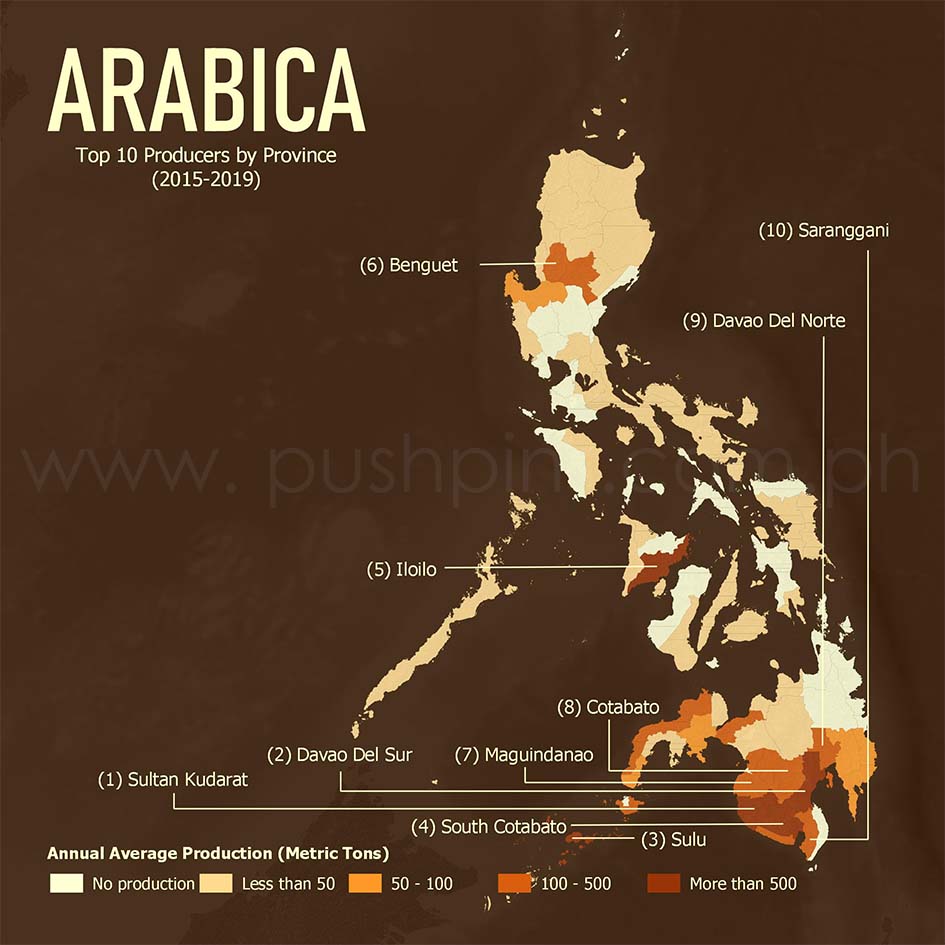

That cup of arabica coffee in your hand? It most likely came from Mindanao. The Southern Philippines is also the top source of arabica beans in the country. Eight of the top 10 producers of arabica in the archipelago belongs to this southern region, with Sultan Kudarat as the leader of the pack. It has consistently topped the list since 1995, and for more than a decade, almost half of the country’s annual yield originates from this province.

Iloilo (Visayas) and Benguet (Luzon) are the only provinces from the top 10 that are outside Mindanao. The two account for 5% and 3% of the country’s annual average production of arabica in the past five years, respectively.

Pinoy pride

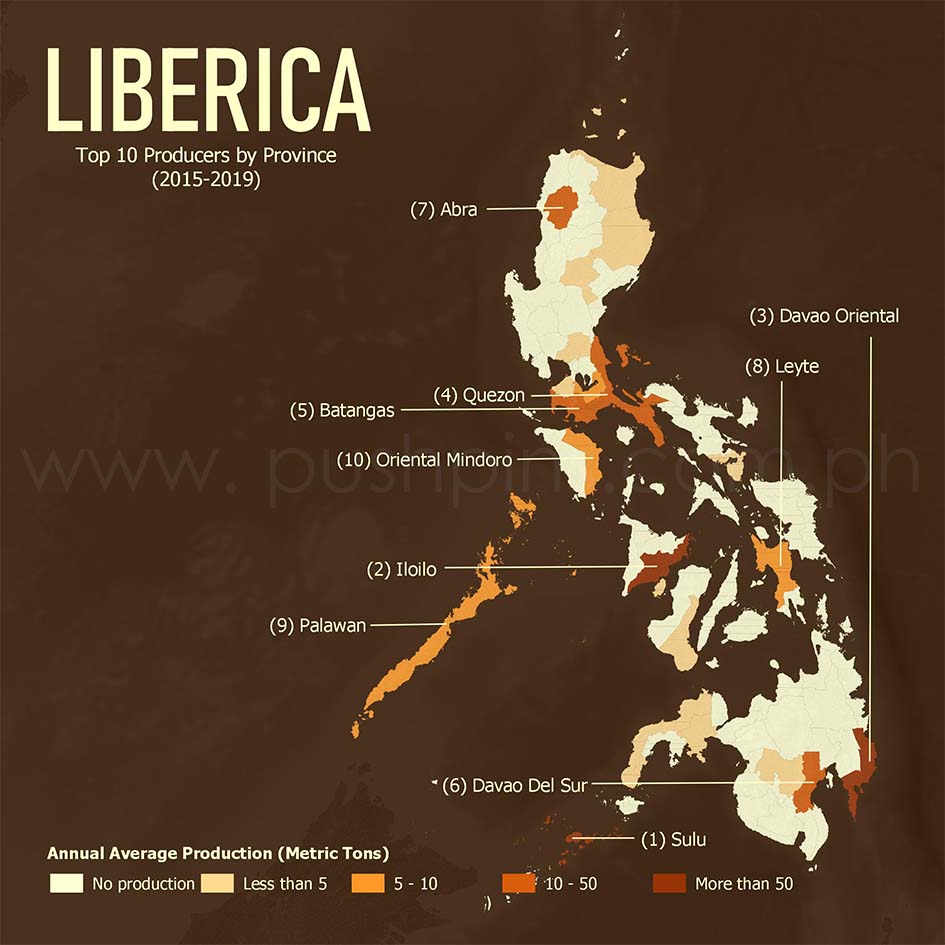

In the Philippines, liberica is known as kapeng barako (“barako” translates to “stud”). Its strong aroma and flavor (akin to jackfruit, according to some South East Asian cuppers) earned liberica its vernacular name.

Over the last five years, half of the top 10 liberica producers in the Philippines are Luzon provinces. Unfortunately, the eruption of Taal Volcano in the region last January 2020 wreaked havoc on the barako plantations in Batangas, the fifth largest producer of liberica in the country. Nearby province Cavite, which takes the 15th spot, also bore the brunt of the eruption.

The Department of Agriculture (DA) estimates that 71% of coffee production in these provinces has been affected, as reported in The Ultimate Coffee Guide Volume XIII, Issue 1 2020, the official publication of the Philippine Coffee Board, Inc. (PCBI). The devastation brought about by the natural calamity will carry over to 2021, PCBI projects.

To help the coffee industry in the region get back on its feet, the DA plans to release funds to encourage the youth to go into coffee farming. The Ultimate Coffee Guide also cites that PCBI is looking at other provinces, like Bukidnon and Sulu in Mindanao, to grow barako in so as to protect this coffee variety.

Playing second fiddle

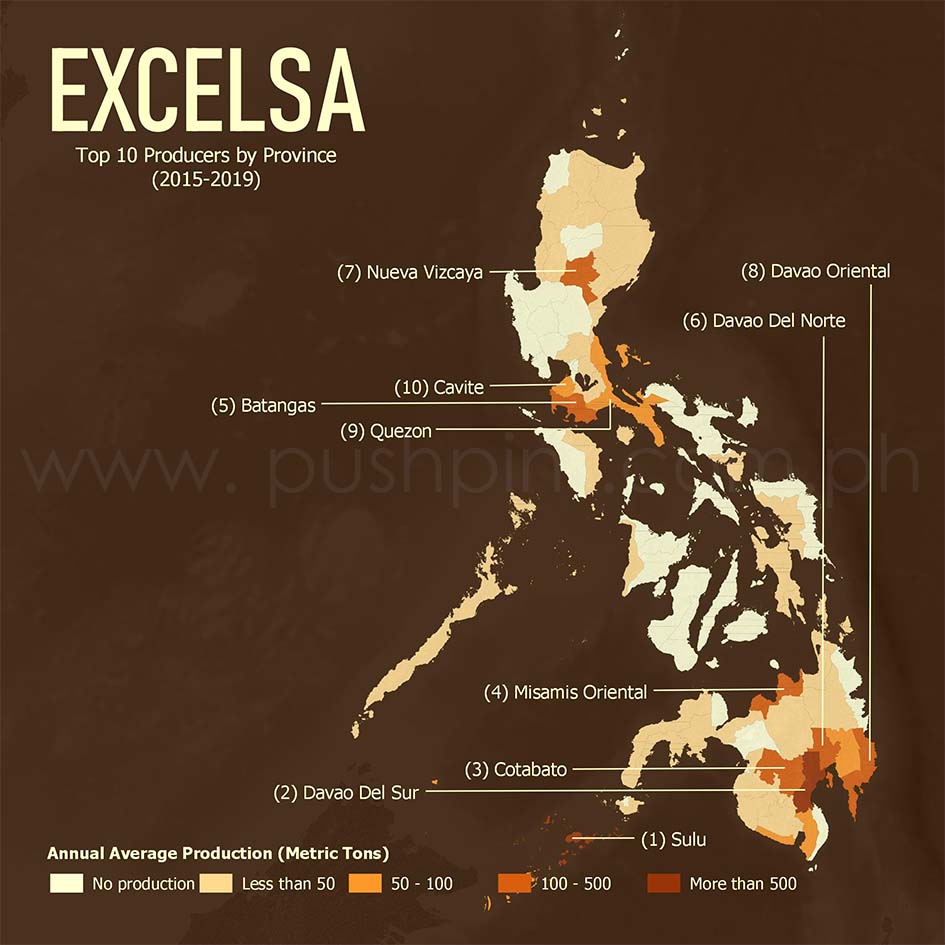

While not as popular as the other three, excelsa still plays an important role in the industry. Its sharp, fruity body and dark notes add complexity and character to various coffee blends.

Excelsa had been considered a separate species until 2006, when British botanist Aaron P. Davis reclassified it under the liberica family. Nevertheless, the two are very much distinct when it comes to flavor profile.

About 85% of the country’s annual average production of excelsa in the last five years comes from Mindanao. Sulu, which is consistently among the top producers of all four varieties, has the highest yield, making up about one-third of the country’s excelsa supply.

Meanwhile, in Luzon, excelsa is sourced mainly from Batangas, Nueva Vizcaya, Quezon, and Cavite. This accounts for about 15% of the nationwide production.

Best brew

What makes a good cup of coffee, well, good? How do you choose from among the many blends of coffee made from robusta, arabica, liberica, and excelsa?

Ros advises, “It’s always nice to try different kinds. I think we’re all creatures of habit, so we order the same thing every time…But it’s also nice to order different things so that you’re able to try other drinks. And then…you develop a taste for what you really like.”

If you want to stick to your familiar brew, say an Americano, order that every time you try a different coffee shop, says Ros. It’s a good way to sample the best Americano brew, ultimately helping you decide what your favorite café is. If you want a more purist approach, drink it black.

A good cup of joe does not happen by chance, though. “The quality of the beans and the roasting are big factors,” says Tala Singson, co-owner of Go Brew!. Careful and skillful brewing and extraction are also important, adds Ros. When it comes to sourcing the beans, Ros puts importance on quality, flavor profile, availability, and the relationship with farmers.

Go Brew’s Rhon delos Santos relates, “What comprises a good cup of coffee is all up to the drinker…Our palates are all different, so a good cup of coffee is what you think it is.” Ros agrees. “There are global standards for coffee and time-tested techniques for extraction, but your happiness is paramount.”

Championing local

Don’t know where to start with your coffee connoisseur journey? These local brands will point you to the right direction. A bonus: they deliver the beans right to your doorstep.

Commune has been serving locally sourced coffee since 2013. Its newest seasonal blends (starts at P420) were born out of the pandemic, with cheeky names like Suspended Reality, New Normal, and WFH (work from home). It’s Commune Blend (starts at P350) is an all-time bestseller.

Kalsada is committed to helping coffee-producing communities through fair trade and close partnerships with coffee farmers from Benguet and Bukidnon. It supplies beans to various coffee shops that promote Philippine coffee. The Kalsada Tasting Pack (P2,000), composed of four kinds of beans sourced from Benguet, sold out in a matter of days.

(Update: As of April 26, Kalsada is no longer be supplying roasted beans. Instead, they will be focusing on supplying local roasters with green beans. You can still get your Kalsada beans supply from Plain Sight Coffee, Habitual, and Yardstick, among other local coffee shops and roasters.)

This young brand offers single-origin coffee beans sourced from local roasters (prices start at P300). Go Brew also works closely with the Philippine Coffee Alliance, with custom-roasts made especially for the brand.

The Den is a specialty café in the First United Building on Escolta, Manila. It recently launched its online café, where you can order beans (P700) sourced from Sitio Naguey and Sitio Belis in Atok, Benguet. The café also offers ready-to-drink cold brew (P150) processed by Kalsada Coffee.

Sourcing exclusively from the T’Boli community in Mindanao, The Dream Coffee advocates ethical partnership with the farmers it closely works with. Its arabica beans (P350) are organically produced from a single estate in South Cotabato.

As more people learn how to brew coffee at home, thereby increasing demand, the local coffee industry will undoubtedly benefit. The next question is: Once most of us realize how easy, economical, and delicious it is to brew our own cup, will we still head out to our favorite coffee shop once this pandemic is over?

—

All information presented here are based on available data and are only meant for an overview of the subject. For in-depth analyses, an extensive study is necessary.

Pushpins is a GIS company in the Philippines. For more information on what GIS is, log on here.